Introduction

Bitcoin is often referred to as digital money, but this is a rough comparison. If Alice pays Bob $10 in cash, Bob has no idea where the money came from. If he then gives it to Carol, she won't be able to know that Alice had it in her possession.

Bitcoin is different because of its public nature. The history of a given coin (more precisely, an unspent transaction output or UTXO) can be trivially viewed by anyone. It's a bit like writing the transaction amount and participants' names on an invoice each time it is used.

That said, pseudonymizing a public address ensures that users' identities are not easily revealed. However, bitcoin is not completely private. Blockchain analysis is becoming more and more sophisticated and is able to link addresses to identities more and more efficiently. Alongside other surveillance techniques, a dedicated entity can deanonymize cryptocurrency users. To address this problem, techniques for unbundling transactions have surfaced over the years.

What is room mixing?

Generally speaking, coin mixing can refer to any activity involving the obfuscation of funds by substituting them for others. However, in the cryptocurrency space, currency mixing generally indicates a service provided by a third party. Typically, service providers take users' funds (and a small commission) and return funds that are unrelated to those sent. These services are also known as tumblers or mixers.

The security and anonymity of these centralized services are of course questionable. Users have no guarantee that their money will be returned to them by the mixer or that the returned coins are not tampered with in some way. Another aspect to consider when using a mixer is that IP and Bitcoin addresses may be recorded by a third party. Ultimately, users give up control of their funds in the hopes of receiving untied funds in return.

A probably more interesting approach exists in the form of CoinJoin transactions, which create a significant degree of plausible deniability. This means that after a CoinJoin, no evidence can link a user with certainty to their previous transactions. Many CoinJoin solutions offer a decentralized alternative to mixers. Although there may be a coordinator involved, users do not need to sacrifice custody of their funds.

What is a CoinJoin?

CoinJoin transactions were originally proposed by Bitcoin developer Gregory Maxwell in 2013. In his thread, he gives a brief overview of the structure of these transactions and how the massive privacy gains can be made without no modification of the protocol.

In essence, a CoinJoin involves combining input from multiple users into a single transaction. Before we explain how (and why), let's look at the structure of a basic transaction.

Bitcoin transactions consist of inputs and outputs. When a user wants to make a transaction, he takes his UTXOs as inputs, specifies the outputs and signs the inputs. It is important to note that each input is independently signed and users can define multiple outputs (going to different addresses).

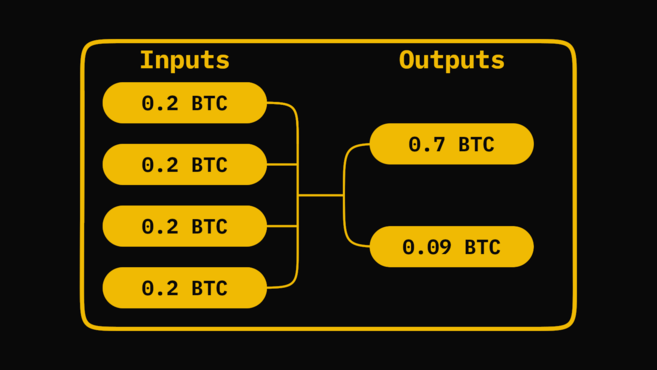

If we consider a given transaction consisting of four inputs (0.2 BTC each) and two outputs (0.7 BTC and 0.09 BTC), we can make a few different assumptions. First, we'll see that a payment takes place: the sender sends one of the outputs to someone and returns the difference to itself. Since they used four inputs, the most important output is probably for the recipient. Note that the outputs are missing 0.01 BTC, which is the fee given to the miner.

It is also possible that the sender wants to create a large UTXO from small UTXOs, and consolidates the small entries to achieve the desired result of 0.7 BTC.

Another assumption we can make is based on the fact that each entry is independently signed. This transaction can have up to four different parties signing the entries. And this is the principle that makes CoinJoins effective.

How does a CoinJoin work?

The idea is that multiple parties will coordinate to create a transaction, each providing desired inputs and outputs. As all inputs are combined, it becomes impossible to say with certainty which result the user belongs to. Examine the diagram below:

Here we have four participants who want to break the link between transactions. They coordinate with each other (or through a dedicated coordinator) to announce the entries and exits they want to include.

The coordinator will take all the information, turn it into a transaction, and ask each participant to sign before releasing it to the network. Once users sign, the transaction cannot be changed without becoming invalid. There is therefore no risk that the coordinator will abscond with the funds.

The transaction serves as a sort of black box for mixing the pieces. Remember that we destroy UTXOs to create new ones. The only link between the old and new UTXO we have is the transaction itself, but of course we can't tell the participants apart. At best, we can say that a participant provided one of the inputs and is perhaps the new owner of a resulting output.

But this is by no means guaranteed. Who can say, when it comes to the above transaction, that there are four participants? Is it one person sending their funds to four of their own addresses? Two people making two separate purchases and each sending 0.2 BTC back to their own address? Four people sending money to new participants or back to themselves? We can't be sure.

Confidentiality through the possibility of denial

The mere fact that implementations of CoinJoin exist is enough to cast doubt on the methods used to analyze transactions. You can infer that a CoinJoin has occurred in many cases, but you still cannot tell who owns the outputs. As they gain popularity, the assumption that entries are all held by the same user is weakened, implying a massive increase in privacy in the ecosystem as a whole.

In the previous example, we say that the transaction had an anonymity set of 4. The owner of an output could be any of the four participants involved. The greater the anonymity set, the less likely it is that transactions can be linked to their original owner. Fortunately, recent CoinJoin implementations allow users to reliably merge their entries with dozens of others, providing a high degree of anonymity. Recently, a 100 person transaction was successfully executed.

To conclude

Coin mixing tools are an important addition to any privacy-conscious user's arsenal. Unlike proposed privacy enhancements (such as Confidential Transactions), these are compatible with the protocol as it exists today.

For those who trust the integrity and methodology of third parties, mixing services are an easy solution. For those who prefer a verifiable, non-custodial alternative, CoinJoin alternatives are superior. This can be done by hand for technically competent users, or by using software tools that abstract the more complex mechanisms. There are already a handful of these tools that are only increasing in popularity as users strive to improve their privacy.