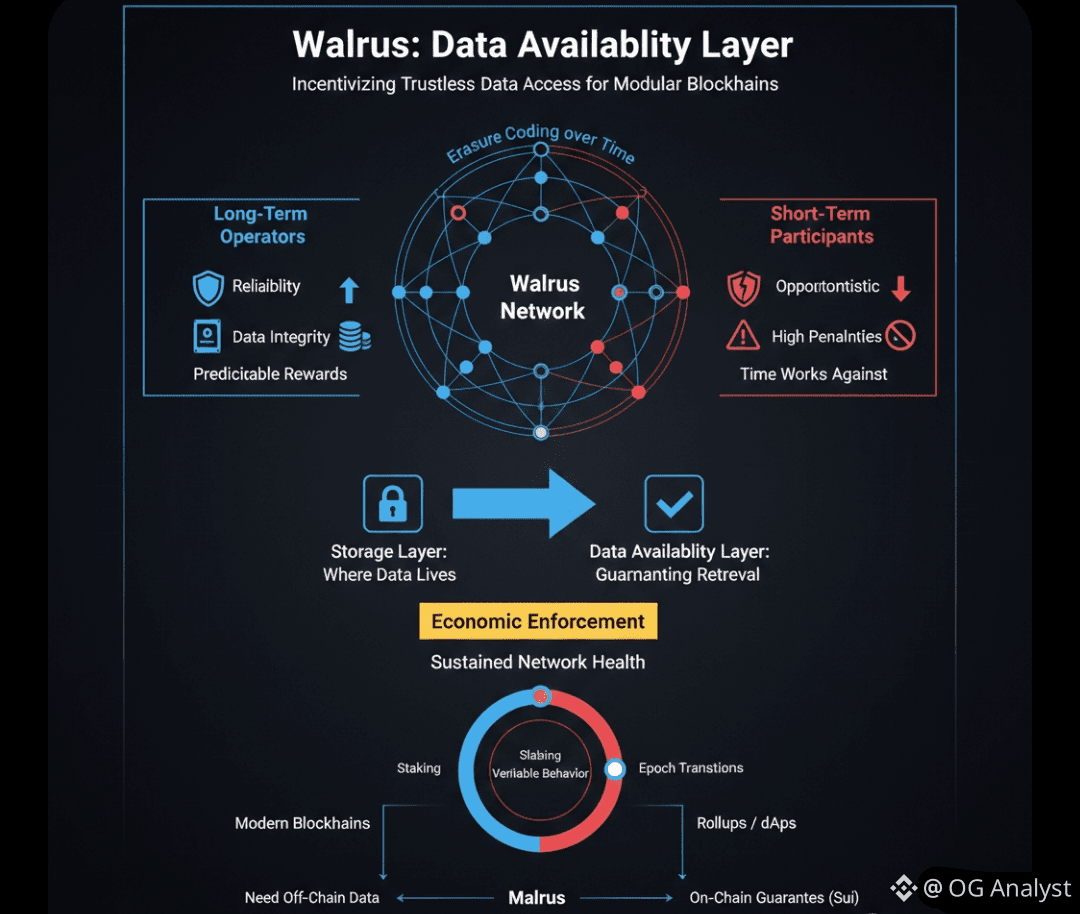

When people first hear about Walrus, they often categorize it quickly: “decentralized storage.” It’s an understandable shortcut, but it misses the more important idea behind the protocol. Walrus is not primarily trying to compete with cloud storage providers or even other decentralized storage networks. It is addressing a deeper infrastructural question that modern blockchains increasingly face: how can large volumes of data remain reliably available without being fully stored on-chain, and without trusting a centralized party to keep that data alive?

Thinking of Walrus as a data availability layer rather than simple storage changes how the entire project makes sense. Storage is about keeping data somewhere. Data availability is about guaranteeing that data can be retrieved when it matters, under adversarial conditions, and over long periods of time. Walrus is designed around that distinction.

Why Storage Alone Is Not Enough Anymore

Early blockchains could afford to ignore large-scale data. Transactions were small, state was limited, and applications were simple. That world no longer exists. Today’s ecosystems depend on rollups, NFTs with rich metadata, on-chain games, AI-integrated applications, and decentralized social platforms. All of them rely on data that is too large, too frequent, or too dynamic to live directly on a base layer.

Traditional storage solutions—centralized clouds or simple decentralized file networks—solve where data lives, but not how availability is enforced. If a storage provider disappears, refuses service, or becomes inaccessible due to regulation or outages, the application built on top of it quietly breaks. The blockchain may continue producing blocks, but the application loses meaning because its data is no longer reachable.

Walrus starts from the assumption that data availability is a core part of blockchain security, not an optional add-on.

The Concept of Data Availability in Walrus

In Walrus, data availability means that the network can cryptographically and economically guarantee that stored data remains retrievable for the duration it was paid for. This is a subtle but important shift. Walrus does not ask users to trust storage nodes to behave well. Instead, it structures incentives and penalties so that remaining honest is the rational choice.

Rather than storing entire files on a single node or fully replicating them across many nodes, Walrus breaks data into large blobs and applies erasure coding. Each storage operator holds only a fragment of the original data. Any sufficiently large subset of these fragments can reconstruct the full file. This means the system can tolerate node failures without sacrificing availability, while avoiding the high costs of full replication.

Availability, in this context, becomes a measurable property. Nodes must prove they still hold their assigned data. If they fail to do so, the protocol can detect it and apply penalties.

Sui as the Coordination Layer, Not the Storage Medium

Another reason Walrus fits better into the data availability category is its relationship with the Sui blockchain. Sui does not store Walrus data blobs directly. Instead, it acts as the coordination and enforcement layer. Metadata, storage commitments, availability certificates, payments, and penalties are all handled through on-chain logic.

This separation matters. By keeping large data off-chain while anchoring guarantees on-chain, Walrus avoids congesting the base layer and preserves composability with other applications. Storage becomes programmable. Applications can reference data objects, verify their availability status, and build logic around them without ever pulling the full data on-chain.

In practical terms, this allows developers to treat data availability as a service backed by smart contracts, rather than as an external dependency held together by off-chain agreements.

Economic Enforcement Instead of Trust

One of the defining characteristics of Walrus as a data availability layer is how it uses economics as a security mechanism. Storage providers must stake WAL tokens to participate. This stake is not symbolic. It represents collateral that can be slashed if the provider fails to meet availability requirements.

From a systems perspective, this changes the nature of risk. A storage provider does not simply risk losing reputation or future business; they risk an immediate, on-chain financial loss. Availability becomes enforceable, not aspirational.

For users, this means that paying for storage on Walrus is closer to entering a cryptographically enforced contract than renting space from a server operator. The protocol itself acts as the arbiter, removing the need for bilateral trust.

Why Walrus Is Especially Relevant for Modular Blockchains

As blockchain architectures become more modular, execution and data availability are increasingly decoupled. Rollups execute transactions off-chain but rely on data availability layers to ensure that transaction data remains accessible for verification and dispute resolution.

Walrus fits naturally into this environment. It does not attempt to execute transactions or validate state transitions. Its role is narrower and more focused: ensuring that data needed by other systems remains available, verifiable, and economically protected.

This focus is what distinguishes Walrus from generalized storage networks. It is not trying to be everything at once. It is optimized for a specific infrastructural responsibility that many modern systems cannot function without.

Practical Implications for Developers and Users

For developers, treating Walrus as a data availability layer means designing applications with clearer boundaries. Data-heavy components can live on Walrus, while execution and logic remain on-chain or in rollups. Availability guarantees can be checked programmatically, and failure cases can be handled explicitly.

For users, the benefit is less visible but more important. Applications built on top of reliable data availability layers fail more gracefully. They do not silently lose data or depend on opaque backend services. Even if individual storage nodes disappear, the system as a whole continues to function.

A Quiet but Necessary Layer

Walrus does not aim to be flashy infrastructure. Its success would likely look uneventful: applications working as expected, data remaining accessible, and failures being handled automatically by protocol rules rather than emergency interventions.

That is often the mark of good infrastructure. By positioning itself as a data availability layer rather than just another storage network, Walrus addresses a foundational requirement of scalable, decentralized systems. It focuses less on where data lives and more on whether data can be relied upon when it matters.

In that sense, Walrus is less about storage capacity and more about trust minimization at the data layer. And as decentralized systems continue to grow more complex and

data-intensive, that distinction becomes increasingly important.